Hi, my name’s Phillip; I'm the founder and chairman of the American Leadership Foundation.

I started the A.L.F. to try to help address an idea that'd been bothering me intensely in the past few years. This particular idea is actually rather strange—and the fact that it bothered me so much might seem even more strange!—but the crux of it can be stated simply:

"The world has never been better than it is today."

That's the center of it, anyway; I've seen it stated in many variations. I think the first form of it that I confronted was this one:

"We are living in the least violent time in human history."

According to this form of the idea, we can call the current era the "least violent" in history because any given human being alive today is less likely to die from violence than they were at any other time in the history of human civilization.[1]

I first encountered that form of the idea in high school, and what bothered me (or maybe just shocked me) the most about it was that just a couple years before, when I was a freshman, we had elected our class's homecoming king posthumously—at age 14, he had been shot to death on an MTA bus as he headed home one night.

"We are living in the least violent time in human history."

What that sentence is saying is actually rather simple: in any earlier era, it was likely that I'd have known more people who had been killed while they were still teenagers. Stated in this way, this strange idea seems remarkable in how it manages to be both bizarrely optimistic and incredibly morbid at the same time.

I continued to think about this idea after high school, when I was working in the supplies warehouse inside Holy Cross Hospital.

One of my co-workers there was a guy named Edwin, who was one of the coolest people I've ever met. I remember watching a rough cut of one of the music videos he was working on as he tried to develop his side career as a singer. I also remember watching him tracing the scar tissue along his arm, showing where a bullet had struck him and ricocheted off his bone before re-exiting, having left a faded but still noticeable line along his tricep in its wake.

"We are living in the least violent time in human history."

With modern medicine and accompanying advances in surgery, Edwin literally lived to tell the tale of being shot, and in fact he still was able to use his arm and hand just fine. In an earlier era, both of those things were much less likely to have been true. In some way, Edwin was living proof of how much better things had gotten.

Of course, the concept of looking at a man's ability to show you the scars from his own bullet wounds as a monument of progress just feels... dark.

"We are living in the least violent time in human history."

The statement is true, but the sentiment rings off-key. The countering thought forming in the back of my head was something along the lines of:

How could this possibly be the best we've ever done?

Something that I think is common to the experience of working in any large hospital like that is the everyday realization that there are a lot of ways to get sick. Sometimes really sick.

When I was there, Holy Cross had not just a general I.C.U., but also a separate intensive care unit just for cardiology patients, as well as one for neurology patients, one for surgical patients, and even one for newborn babies who were, of course, particularly vulnerable to all kinds of acute health issues. That's not to mention the oncology unit, or the hemodialysis unit providing both acute and chronic care, or any of the other units that provided acute hospital care without being labelled "critical".

Each of these separate hospital units was its own example of the miracle of modern medicine as we know it today: doctors and nursing staff giving people their best chance to fend off illnesses that would have likely killed them in any previous century. On any given day you might see a patient being discharged to go home only days after their heart had literally stopped. The power of those moments could be overwhelming, if you stopped to think about it.

Those moments were generally the end points of a struggle, however, and that kind of struggle is never easy. People don't go to a hospital when they aren't in any pain or discomfort, and unfortunately just entering those doors won't immediately alleviate that pain either.

And there are still a lot of things we just can't cure.

I've thought about those various hospital scenes after leaving, especially when connecting with people who've lost a parent or loved one to heart failure, kidney failure, cancer.

How could this possibly be the best we've ever done?

There's actually a fair bit of money pouring into emerging medical research right now. From 2013-2016, when I was going back to school to get my bachelor's degree at the University of Maryland, spending on medical R&D from all sources increased around 20% in total,[2] and biomedical start ups are an emerging priority for various venture capital funds, with leading firms like Union Square Ventures and Andreesen Horowitz being quite vocal about their interest in driving even more money into the industry as promising new technologies continue to emerge.

Unfortunately, the cure for cancer doesn't seem to have a market clearing price.

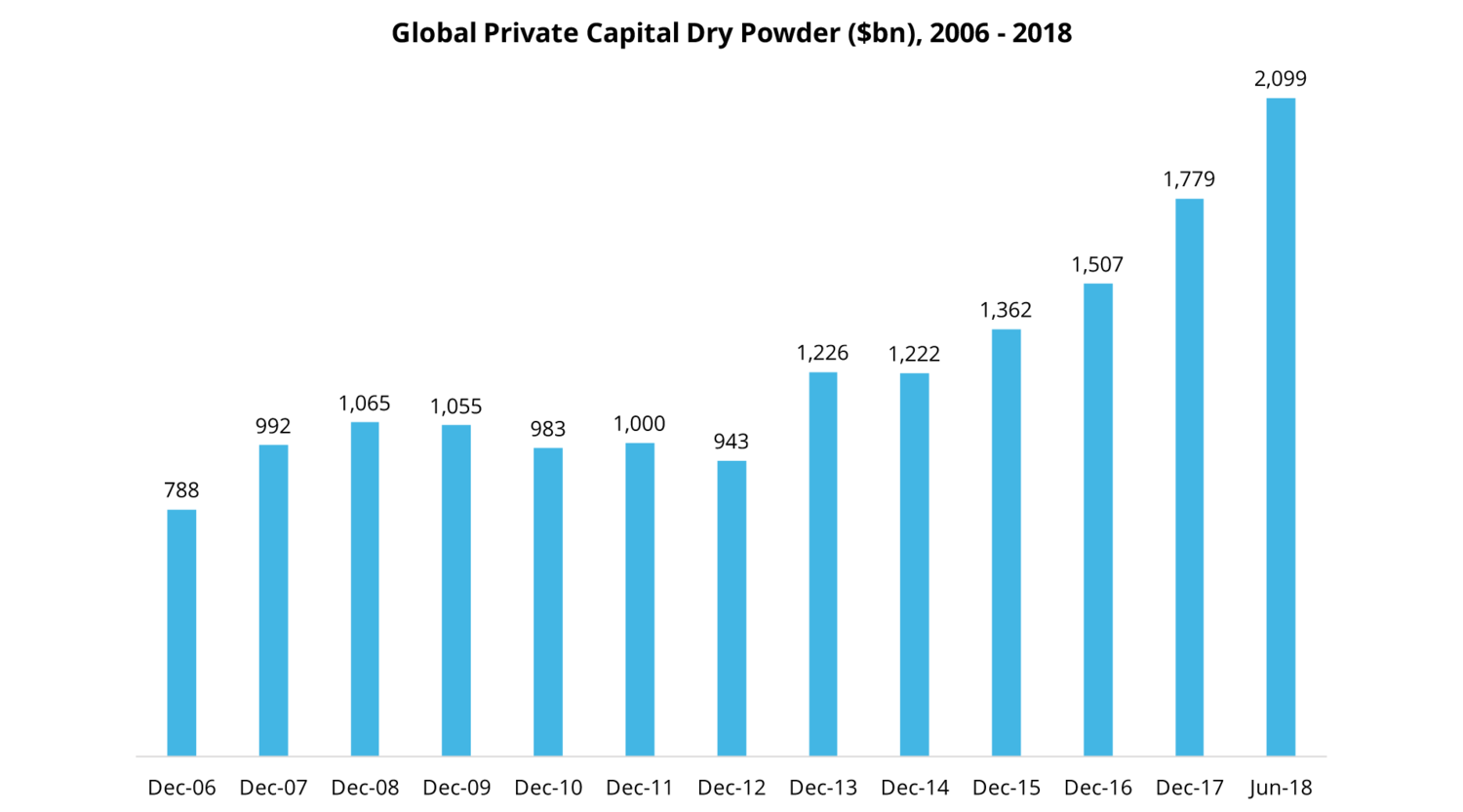

In fact, the argument could be made that money is moving into these speculative research areas only reluctantly. Interest in so-called "hard science" start ups is a rather new phenomenon, flowing from a somewhat surprising issue where—to the financier's perspective—there is actually far too much capital in the world right now, with too few obviously sound investments. Private capital's stock of so-called "dry powder" (highly liquid, cash-equivalent securities that generally represent money not actually being used for anything) surpassed $2 trillion in 2019,[3] as global investors continued to accrue profits they were not able to put to any productive use. So even as billions of dollars flow into biomedical research, there's literally trillions of dollars sitting on the world's collective balance sheets, not even generating enough returns to keep up with inflation. That enormous sum of loose capital puts pressure on the financial system to find new ventures to fund, even when the chances of success aren't as clear.

The stage is properly set now that any real medical breakthroughs that emerge are more likely than not to be picked up and really run with by the healthcare industry, probably with government support along the way. All we're missing are the actual breakthroughs; the main thing we need is just a group of talented and motivated people to do the actual work.

Which leads me back to the question I had been asking myself: how could this possibly be the best we've ever done? When I was younger I didn't have any real cohesive view of how the world or its resources were organized, and I tended to view things as much more static: things today are probably the way that they were before and probably the way that they will be in the future. What's more, I had an un-examined belief that most people generally have similar experiences of the world, and that it was very rare to have the kind of life that most other people wouldn't relate to. The combination of these two ideas can make it easy to think that it's both difficult and unusual to make a difference in the world, and that we should resign ourselves to the understanding that such changes will probably be made by other people; as I've gotten older, I've come to believe the exact opposite of all these points is closer to the truth.

I've been fortunate to find a career path that fits me well, and it's afforded me a whole host of surprising experiences I've been able to learn from, as well as the chance to meet and work with an inspiring array of very talented people in all walks of life. What I've learned from all of it so far could probably be distilled down into this idea: success is just the absence of failure. Our lives are filled with so many attempts at so many different things, and people say we "succeed" in those efforts when we simply don't fail.

Success can feel arbitrary; success is usually finite and temporary; it's hard to realize success while it's actually happening; success can come at any time, as long as you're pushing to do something that you might fail at.

Most importantly, it's always possible to build off of success, whether it's your own or someone else's. Most things in our lives and our society are the way that they are just because they're in some way an improvement on what came before, but further improvement is always possible.

So yes, I believe it's true: "the world has never been better than it is today." But only because we haven't been able to build a better one so far.

We don't just need breakthroughs in medicine. We need enormous advances in energy production and storage if we're going to counter climate change and supply the world's growing needs for electricity; we need better ways to model risk and uncertainty as our financial planning becomes more speculative; we need real innovations in mass communication and civic organization as we see ever more political gridlock.

And then, as John F. Kennedy said in his famous moonshot address, we need "to do the other things, too." We need to try to live kind and healthy lives, and we need to try to be good friends, loving family members, and strong members of our community. We need to care for each other, and enable each other to live better lives.

These are the challenges that define our lives, and we will only ever succeed at overcoming them if we simply refuse to give up. We will need the resolve, resources, and organization to surpass these difficulties that can only be found in other people—and we'll need leaders to channel that.

It's in this tradition that I started the American Leadership Foundation. The vision is for an organization that will support and nurture emerging leaders who will ensure that, even if the world has never been better than it is today, it will be even better tomorrow.

Thank you,

R Phillip Castagna

Chairman, American Leadership Foundation

A claim probably made most famous by the 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature by Steven Pinker (ISBN 978-0-670-02295-3) ↩︎

Statistic based on a report from Research America: U.S. Investments in Medical and Health Research and Development 2013-2016 ↩︎

$2tn figure initially seen in this research note from Preqin, but I've verified it on background with various friends in private capital ↩︎